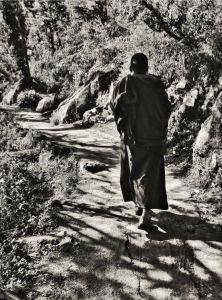

Right at the end of our last post, I mentioned – in an almost off-handed manner – that the hermitage has moved. Better to say the hermits were lead by the ever not so subtle universe to leave our refuge of a year for the safety and seclusion of another abode a few hundred metres away.

Why? Why did the hermits have to move? Well here’s the thing, the owner of that space that had graced us with its protection for that year decided to revive his on and off again campaign to sell the property. And with great success too: very soon there was a buyer very keen to move in ASAP

So, the search was on for a new abode to house the hermits. Cutting a long story short, and leaving out a multiplicity of praises, gratitude, and details, here we are.

Now you know why we moved into a new hermitage. Or do you? You have a few of the facts about how the process of us moving actually manifested in the material world, but as to proper answers to the why questions? You’ll agree that it’s all a bit vague, mundane, and that I haven’t given any answers to why at all.

That’s because I don’t know either; no idea at all.

It’s true, there were some unusual obstacles and pressures – but aren’t there always for everyone as they negotiate and try to manage their lives in the world?

And I could add that the timing could have been better – see above rhetorical question for my response to this one.

No. Like so much (actually everything really) that happens in the on-going, non-stop re creation of the physical world (constant flux, change,seeming chaos, conflicts, setbacks, advances, ups and downs) as it flows along in its own way at its own pace, I have to admit, its a mystery to be unravelled. Or not: there are some who would dare to label this constant re creation, God’s will.

So, we can ask why here? Why now? What’s the lesson to be learned from the move to the new hermitage.

Or we could just tell ourselves that that’s just the way the Cosmos does things. By any standards it’s been a no hitches, no hassles, change of address. But let’s not get distracted by dualities: It is what it is, as I like to say.

And there’s no good or bad, but thinking makes it so.