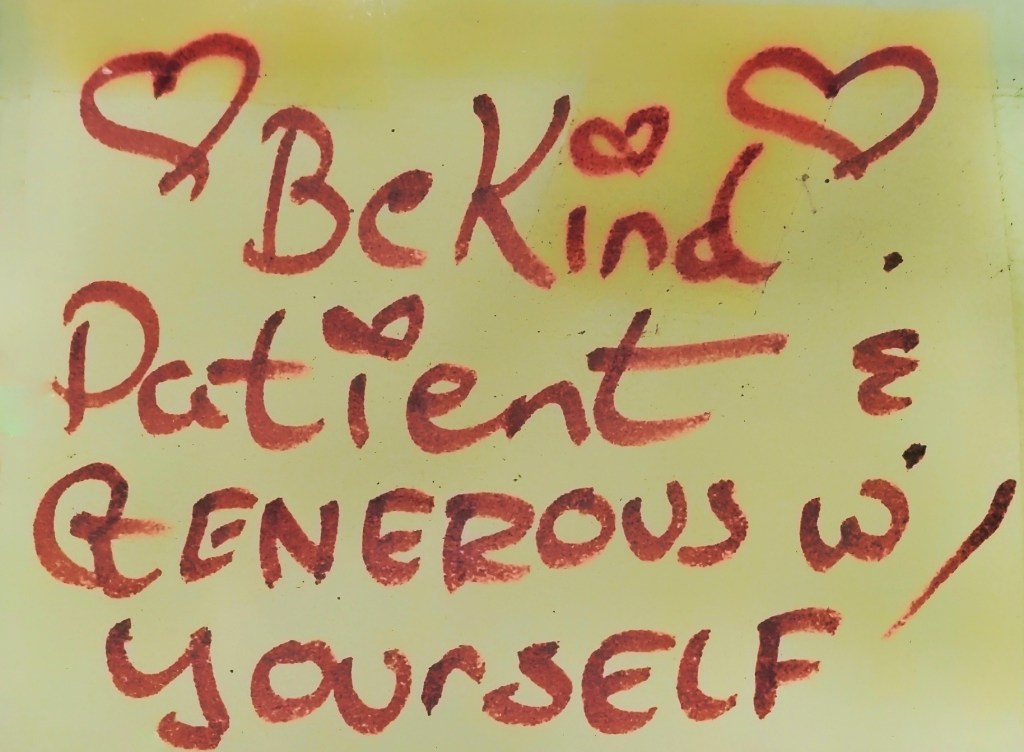

In my last post, I reflected upon a lovely Buddhist mantra, an invocation for peace and happiness for all beings (Lokah Samastah Sukhino). We discovered along the way, that it is no ordinary mantra: it actually amounts to a solemn promise to contribute to the peace and happiness of others (and Self obviously).

Then we thought about how to actually go about acting on this promise: Be kind. That’s what I came to. That’s all that is required. But, as you will recall, being kind sounds easy but quite often isn’t. The Buddha himself came to our rescue with The Eightfold Path,

At the end of that last post, I declared I would devote this next one to looking at Right Understanding, the first of the principles in The Eightfold Path. I said I would just sit at the keyboard and see what emerges as I thought about what is Right Understanding.

Before we get started, let me make the point that The Eightfold Path is not a kind of ‘to do’ list where you tick off one item and move onto the next. The Path is more about integrating the principles into our lives, letting them overlap when they do and moving forward in one area, while (possibly) moving backwards in another as our lives unfold with all the usual twists and turns.

The Eightfold Path is a life-long (some would say lives-long) process; don’t think in terms of goals to be achieved.

Does this mean we will need to explore all eight principles on the Path? Well, we’ll have to see how this evolves over time. Although as I say it’s not a to-do list, I think it more than possible to at least think about the principles or steps on the Path one at a time.

The second thing to say by way of introduction is this: As I mentioned in my previous post, there are virtually unlimited places on the internet where one can source The Buddha’s Teachings, including many commentaries on The Eightfold Path.

I’ve made no use of any of these sources. I have sought only to put down some of my own ideas and learnings, as well as just letting my heart have its say.

If in that process I’ve made any errors of any kind, forgive me. I merely follow The Buddha’s own instruction: Don’t take my word for it; Ask questions; Do your own analysis; Think for yourself.

Now that’s all out of the way, let’s just describe briefly the Four Noble Truths. This is necessary because the injunction to follow The Eightfold Path, comes in the Fourth of those Noble Truths.

Putting them as succinctly as I can, The Four Noble Truths are as follows: The first truth tells us that life is suffering, the second that the cause of suffering is desire (or we can also say attachment), the third that there is a cure for suffering and the fourth tells us what that cure is.

That’s where The Eightfold Path comes in: it’s what you might call The Buddha’s prescription for the alleviation of suffering. At this point I would like to suggest that if you are not familiar with the Four Noble Truths, please take some time to check out the topic for yourself.

The Eightfold Path does, as I mentioned last time, in fact sound very easy when put it in list form like this:

- Right understanding

- Right thought

- Right speech

- Right action

- Right livelihood

- Right effort

- Right mindfulness

- Right concentration

Remember, though, as I said, it’s not a to-do list we can work through one item at a time. Or perhaps we can put it another way: It is possible to work on one item at a time, but it’s not about getting that one completed before one can move on to the next item on the list.

The first step on this Noble Path we have embarked upon is Right Understanding. Actually it’s not only the first, it is the ongoing one; and it is the final step also on this particular Path of Liberation. And it seems to me that I’m right in this: my life has been one continual search for undetstanding.

Not many people know this, but I spent some time working as a journalist. One of the fundamental principles (aside from telling the truth of course) that I followed was the, Who? What? When? Where? Why? and How? set of questions.

Now, I wouldn’t say that it was necessary to ask every one of these questions in every situation. But, as a general rule, they served as a useful guideline to getting as much information on all relevant aspects of an event, a person, or whatever the subject of a story was. And I have to say that I find myself quite often using this list or some varient of it when I’m trying to understand or figure out something.

Why those questions? Where do they lead? What am I trying to do by asking them? How do they help me? (See what I mean? I can’t help myself) If we sum it up, then we would say that asking the WWWWWandH questions have the potential to lead us closer to understanding.

Let’s say you are unhappy with the work you do on a daily basis. You don’t understand why; After all, it pays okay; the hours aren’t too onerous, the work itself is fairly easy as work goes. What’s the problem then? You just don’t understand. You know there’s something not quite right, but you just can’t put your finger on it.

Who is doing that job? I am, you say. But, really, who are you? Is it you doing the job or just a part of you that you kind of section off from the real you for the working day?

What are you doing that makes you unhappy? Is it being in that workplace? Is it the work itself? It might be ‘okay as far as work goes’, but is it really okay?

When are you at that job? I guess this question is about how many hours, what percentage of your life you spend doing that job. And, even more to the point of the when question: When are you really there? How much of your work day are you actually off somewhere else? (refer to the where question)

Where are you? Are you where you want to be? And, kind of getting back to the Who question, who is it that’s there? Is it the real you? Or is it that sectioned off bit of yourself you access during work hours while the real you is off somewhere else?

Why are you doing that job/work? Well most likely your answer will be something like: I have rent to pay, food to buy, bills to pay, family to support. Well, those answers have to do with what you do with the money you earn from doing that job. The question lingers: Why are doing that job? I mean, the real you; why?

How can you be happier at your work? By now you’ve got the hang of this. If you have answered all the W questions then you will already be getting some clues about the answer to the H question.

Asking variations of this set of W and H questions can help us in many aspects of life where we seek understanding. They don’t have to be put as formal questions, and they don’t have to all be asked in every situation. Also they don’t have to be thought based queries either, if you know what I mean.

The answers may well come by simply asking the question, and ‘sleeping on it’. By that I mean you don’t have to tirelessly mull over a question. Meditate on it, think about it, of course, but then forget it consciously and let the answer come to you. And, of course you can always literally sleep on it.

There’s a small art gallery in a desert mining down almost in the heart of Australia. On their window they used to have a quote by Claude Monet:

I know we aren’t talking about art here (or maybe we are?), but I think this quote applies to many of us as we try to understand our lives and our place in the world. Especially when it comes to what makes us happy. All of us spend a lot of time, not so much pretending as in going through the motions. That’s because sometimes it’s just too hard to try and understand.

But, keep at it. Ask the questions but don’t worry about the answers: they will emerge when they’re ready. True understanding is close to love, as Monet says.

Peace to you from me