Perhaps shameful is too strong a word, but that’s kind of how it feels. You see, I’ve been thinking of giving up on the book I’m reading at the moment. And you are thinking, this is a big deal? If you don’t like it, put it aside and try something else.

Yes, excellent advice, thank you. And usually that’s what I would do. In fact now I think about it there was a time when I would force myself to complete a book, even if I wasn’t enjoying it or was bored with it. But I learned a long time ago that this is a waste of time, waste of mind, waste of energy, and unfair to me.

Yet, on this occasion, I started to have some thoughts that took it a bit deeper. It’s true to say that I’m a bit bored with this book; it’s as if I’m not overly interested in the story the author is telling, and in the way she’s telling it. As well I had this feeling that the book was ‘ordinary’: meaning that it was a kind of day to day telling of a segment of a life with its mundane and routine elements included along with the ‘good bits’.

And it was that feeling of being not so interested that got me thinking. The author’s vocation, thinking, activities, and the subject of the book itself, is exactly in line with areas I am very interested in reading about, not only for entertainment but for my learning, for my own spiritual journey and way of life.

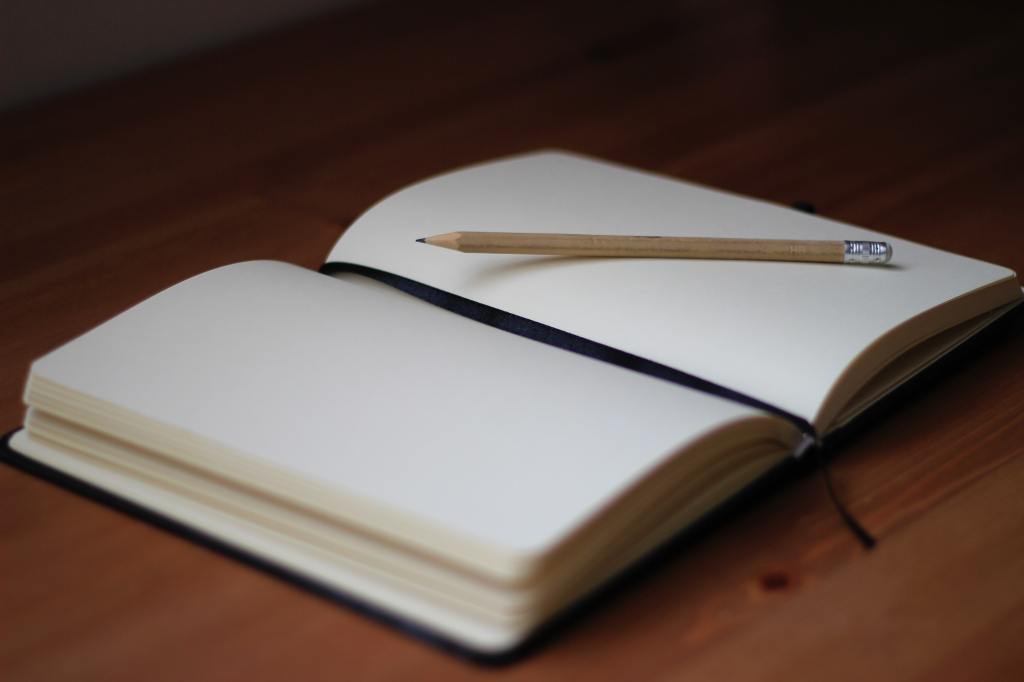

The way she’s telling it? Now, this one got to me even more. The book was put together after the author’s death and is made up of extracts from the author’s journals and from the many letters she wrote to family and friends during the period of her life the book covers.

That’s what I do isn’t it? Keep a journal? Write letters? These and the many many blog posts (which in a way are a lot like letters, and even journal entries do you think?) I’ve written over many years, and the journal I’ve been keeping for most of my life, are the core of at least the personal writing I have done over my lifetime. By rejecting this book I started to feel that I was rejecting my own, for want of a better word, genres.

Or, worse than that, I’m rejecting the invitation to share a life. And illogically I’m rejecting the life story and insights of a person whose own experience I actually value for my own quest and from whom I could learn a great deal.

And what about the feeling of boredom and that the book was too ‘ordinary’ and mundane? Well, to borrow a well-worn phrase, this really does take the cake. I mean if you were to look at much of my past writings and look at my photography blogs from times past, you would see that one of my main statements of belief was:

There are no ordinary moments, nor are there any ordinary people.

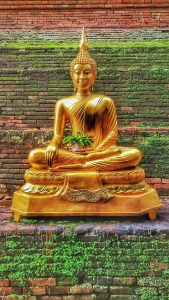

And I still believe this. Indeed, spiritual practice and study has only deepened my instincts that all there is is the moment; all there is is all the beings of the world experiencing that ongoing presence, that never-ending moment. There can be nothing in the least ordinary about that.

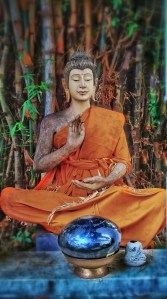

I’ve saved the best – or is it the worst? – for last: what the book is about. It tells the story of a three year period in the life of a person just out of university who looking for a deeper meaning to life and to finding a true course for her life, travels from her home to Japan and enters a Zen monastery to become a monk.

Her journals and letters give the reader an intimate and in-depth account of her experiences: what she learned; insights into the language, culture, and history of Japan and Zen itself; the people she met and knew, her own feelings and reactions to what was a huge shift in her life.

After three years the author left the monastery to travel slowly back to see family at home. Sadly she was killed in a bus crash along the way.

Pretty much everything that has to do with living a life. And here’s me rejecting it because it was ‘ordinary’ and some details were ‘boring’.

So, I’m going to stay with this book. It’s taught me a lot already, and I think there is more there for me. Perhaps, I can better put into practice by own so strongly held idea that there are no ordinary moments or ordinary people.

Peace and love from me to you