These last few days I’ve been researching and thinking about an idea for a blog post. But I’ve come to realise that I am grossly underqualified to write about the topic I had in mind. Let me put it another way: I am completely and utterly unqualified in any way whatsoever to go there. In fact, after all the research, I think I’m going to disqualify myself from ever going there in writing.

However, I’m a great believer in the idea that no quest for knowledge is ever a waste of time or effort; there is always something to be learned. During my research I came across a topic I believe I am qualified to discuss, as it forms an integral and vital part of my own personal spiritual practice.

Why I’ve decided to write this post, though, is because I made a discovery that lead to an insight that I know will lead to a great progress in that practice. It’s nothing new, not really, but it was one of those occasions we’ve all experienced of ‘I knew that, but now I really know it.’ For me, it was a realisation of something that till then had been a nice cosy theory and belief.

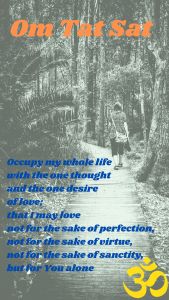

Bhakti Yoga is that practice. It is really a key foundation, a valuable component of my spiritual life.

Wikipedia opens its entry on Bhakti Yoga (see the link just above) with a description of the practice that mirrors what I think is the traditional understanding of Bhakti Yoga:

Bhakti Yoga (also called Bhakti Marga, literally the path of Bhakti) is a spiritual path or practice within Hinduism focused on loving devotion towards any personal deity.

In the same entry there is a description of the origins and meanings of the two words, Bhakti and Yoga:

The Sanskrit word Bhakti is derived from the root bhaj, which means “divide, share, partake, participate, to belong to”. The word also means ‘attachment, devotion to, fondness for, homage, faith or love, worship, piety to something as a spiritual, religious principle or means of salvation’.

The term Yoga literally means “union, yoke”, and in this context connotes a path or practice for ‘salvation, liberation’. yoga referred to here is the ‘joining together, union’ of one’s Atman (true self) with the concept of Supreme Brahman (true reality).

In other words, those called to a religious or spiritual life, practise Bhakti Yoga whenever they pray or otherwise express devotion towards their personal conception of God, or the Divine. This particular definition seems to be saying that such a conception of the Divine, or God, is in the form of a personal deity who is a kind of representative of true reality, which the devotee is aspiring to join with.

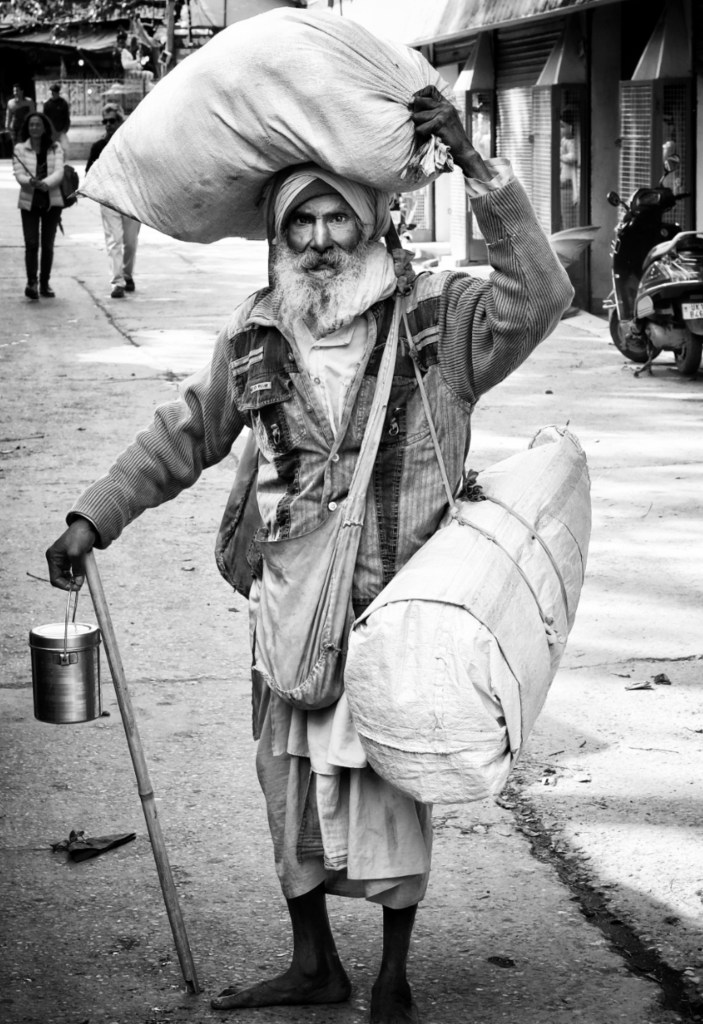

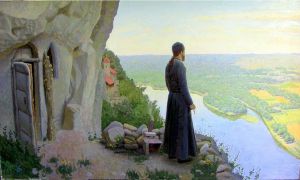

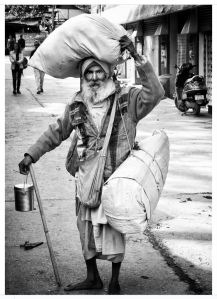

Some Bhakta Yogis are full-time, full-on practitioners. People like contemplative nuns or monks, hermits who retire from the world into seclusion. Anyone basically whose entire life and activities are spent in devotion.

So, when I discovered all this, I became intrigued; I decided to go off on a tangent and explore the word Bhakti itself. Wikipedia has a separate entry for the word on its own:

Bhakti is a term common in Indian religions which means attachment, fondness for, devotion to, trust, homage, worship, piety, faith, or love. In Indian religions, it may refer to loving devotion for a personal God

…

is often a deeply emotional devotion based on a relationship between a devotee and the object of devotion.

…

In ancient texts the term simply means participation, devotion and love for any endeavor.

May refer to devotion to a personal god? While I thought this entry doesn’t contradict our first quote above, it does seem to broaden, and deepen, the meaning of Bhakti. Expand might be the better word.

It struck me that that object of devotion might be anything. Or even everything. You see? I told you it wasn’t a new idea. It’s just that it’s resonated deeply within me now. It appears that the object of Bhakti Yoga practice doesn’t necessarily have to be a ‘personal god’.

Many many people would say ‘I like animals’ or ‘I think we should save the world’. But, while that may imply a kind of love for or at least a fondness for, I think Bhakti is something more – actually several somethings more!

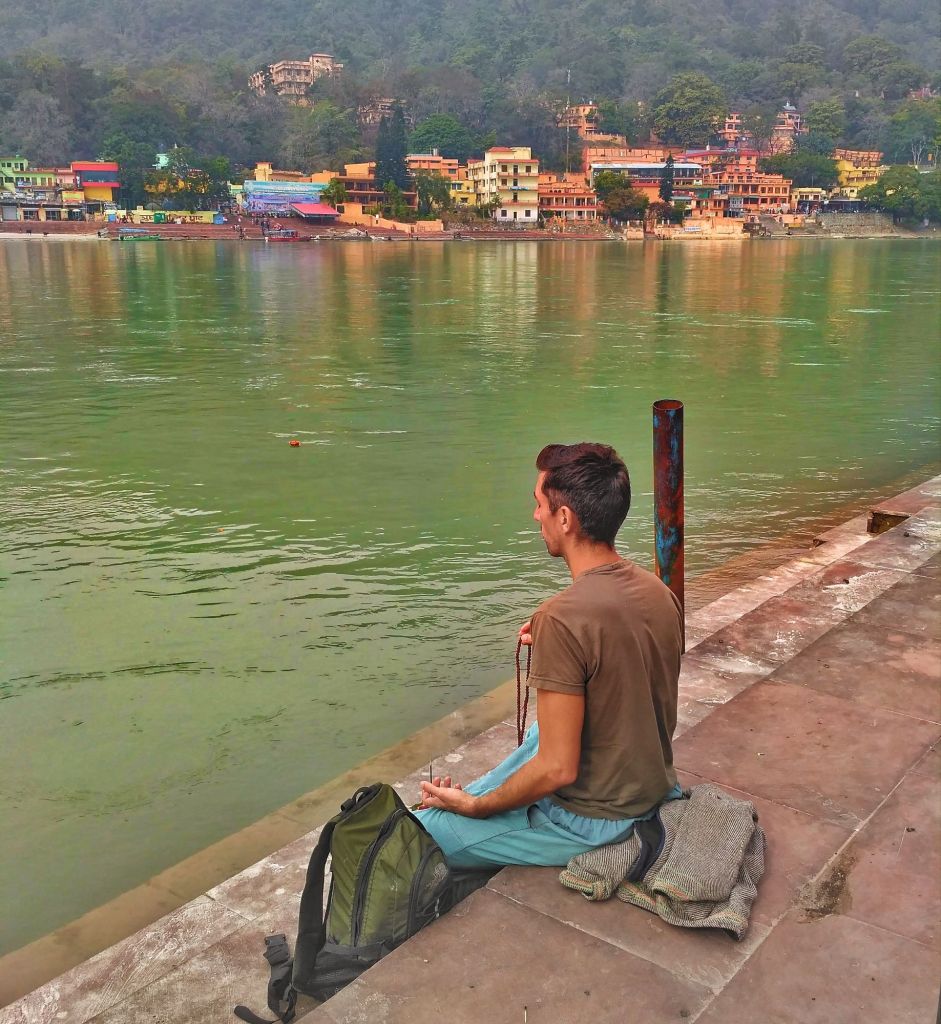

For example, some people have a particular attraction to and love for, the ocean, or it might be a river they view as, if not sacred in a religious sense, then as special to them in some deep, comforting, even therapeutic way. Others have similar relationships with and feelings for trees, or even a particular tree.

Animals as either individuals or as a species or group, can have the same appeal and call to other people. Then there are those who feel strongly in their hearts you could say, that Earth itself is a sacred object, or others have a knowing that the planet is a living entity and worthy of our devotion.

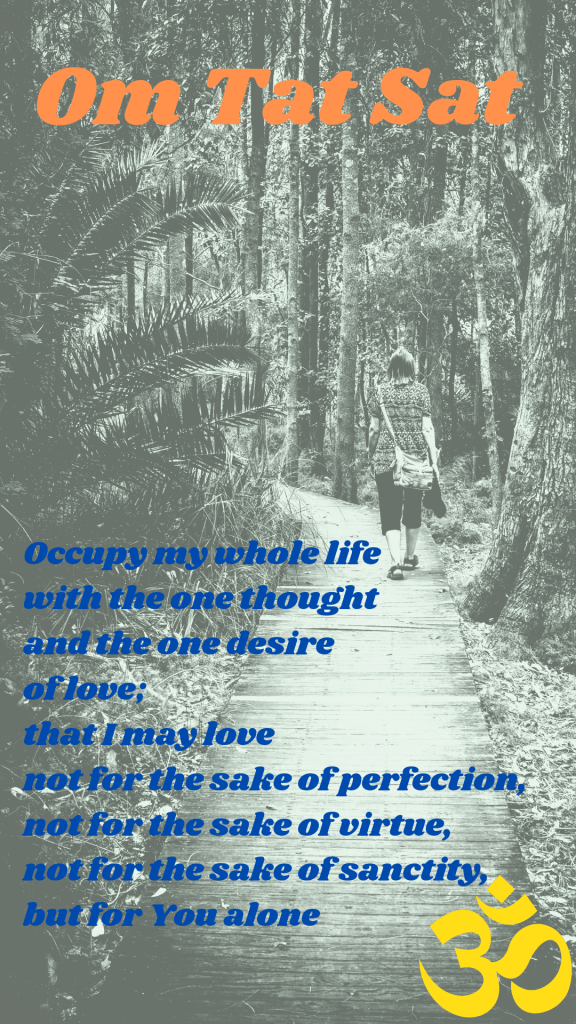

Bhakti begins with love and devotion, which is about caring for, affection towards, loyalty to, emotional engagement with the object of devotion. But even more than that, there is faith in that object of devotion; faith as in trust, confidence that the love is real, that the ‘relationship’ is sound and real.

Homage and worship too are key aspects of Bhakti. The deep inner feeling we have towards a thing, person, or other being, that is beyond what we normally call ‘love’. It’s about seeing and actually realizing ‘in our hearts’ our desire to be merged or united with that thing, person, or other being.

Actually, seeing that word other just now got me thinking. I had to go back and reread our definition of Yoga up there near the beginning. It says Yoga means ‘union, yoke’. It goes on to add: yoga refers to a ‘joining together, union’.

This passage seems to be suggesting that Yoga (in our case Bhakti Yoga) is both an already existing union, and a process of joining together to achieve union. One thing I would say here is that in my practice of Bhakti (and love as a general thing to strive for and be) it’s both.

But, in the end, it seems to me that the process or practice, the path of Bhakti, serves to awaken us, to assist us to acknowledge, recognise, and realise in that really knowing way, our pre-existent true nature.

That true essential nature can be said to be the reality of our oneness with all things, living and non-living. And their oneness with us too of course. In fact, by putting it that way, I’m saying there is only one, or oneness. What’s that expression? One without a second.

May you be a Bhakta Yogi. Or, perhaps you already are one?

Love and peace from Paul the Hermit

Life has manifested itself as the multitudinous forms that comprise the universe. It is the one Universal Life, Power or Shakti (the laws of the universe or natural laws) that controls, guides and actuates all movements and activities in all beings, creatures and things.

— Swami Ramdas